home is a four letter word

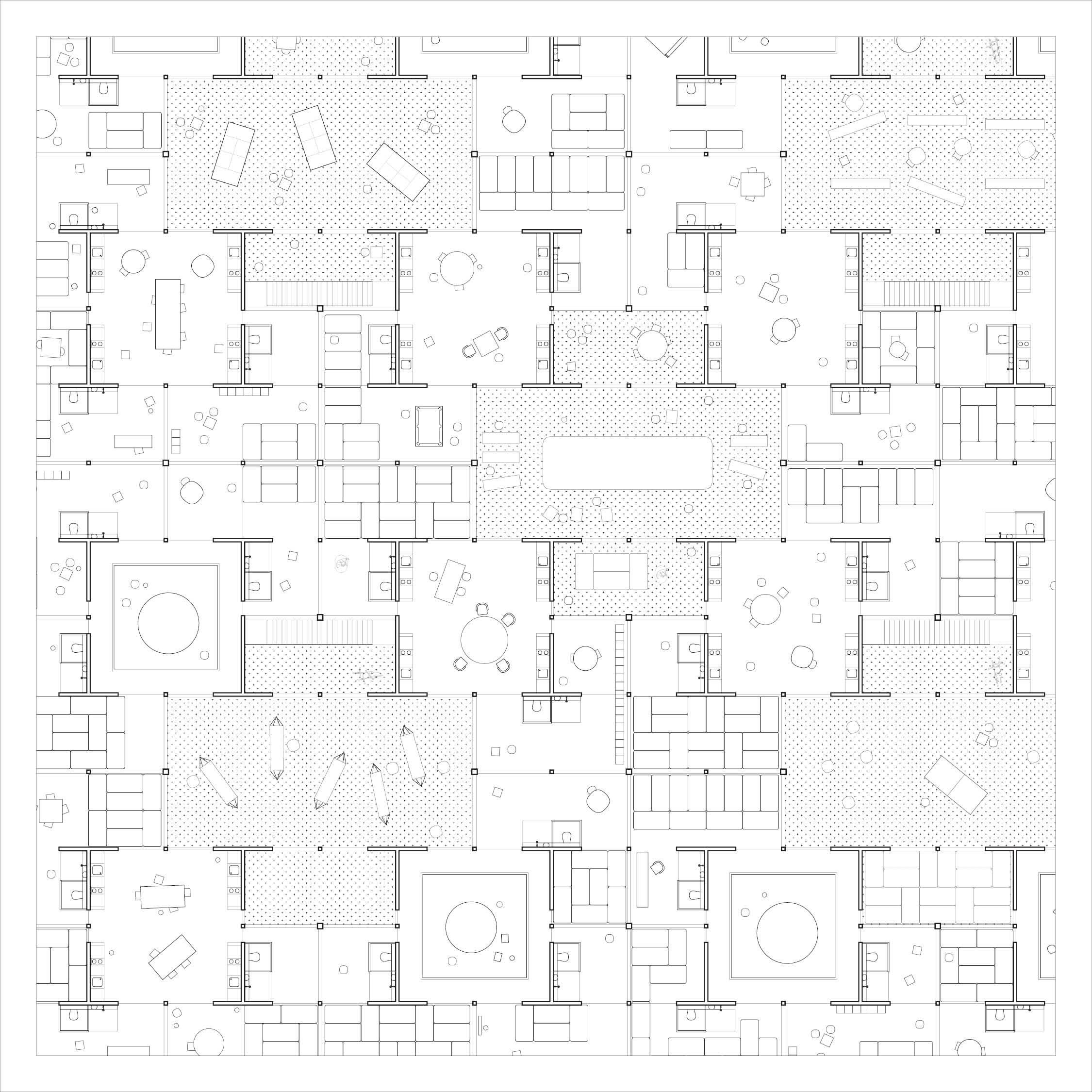

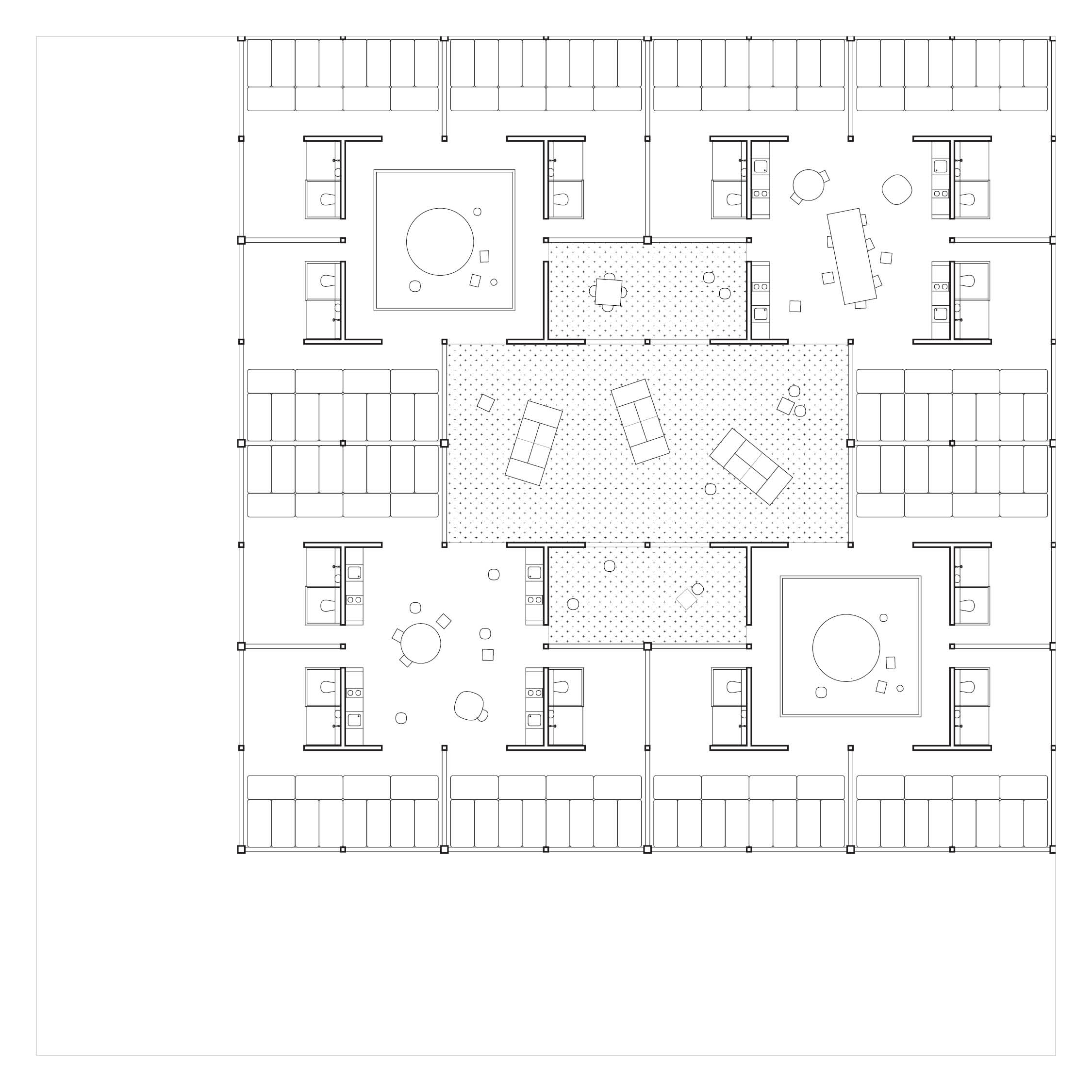

floor plan: bed-room-less domesticity

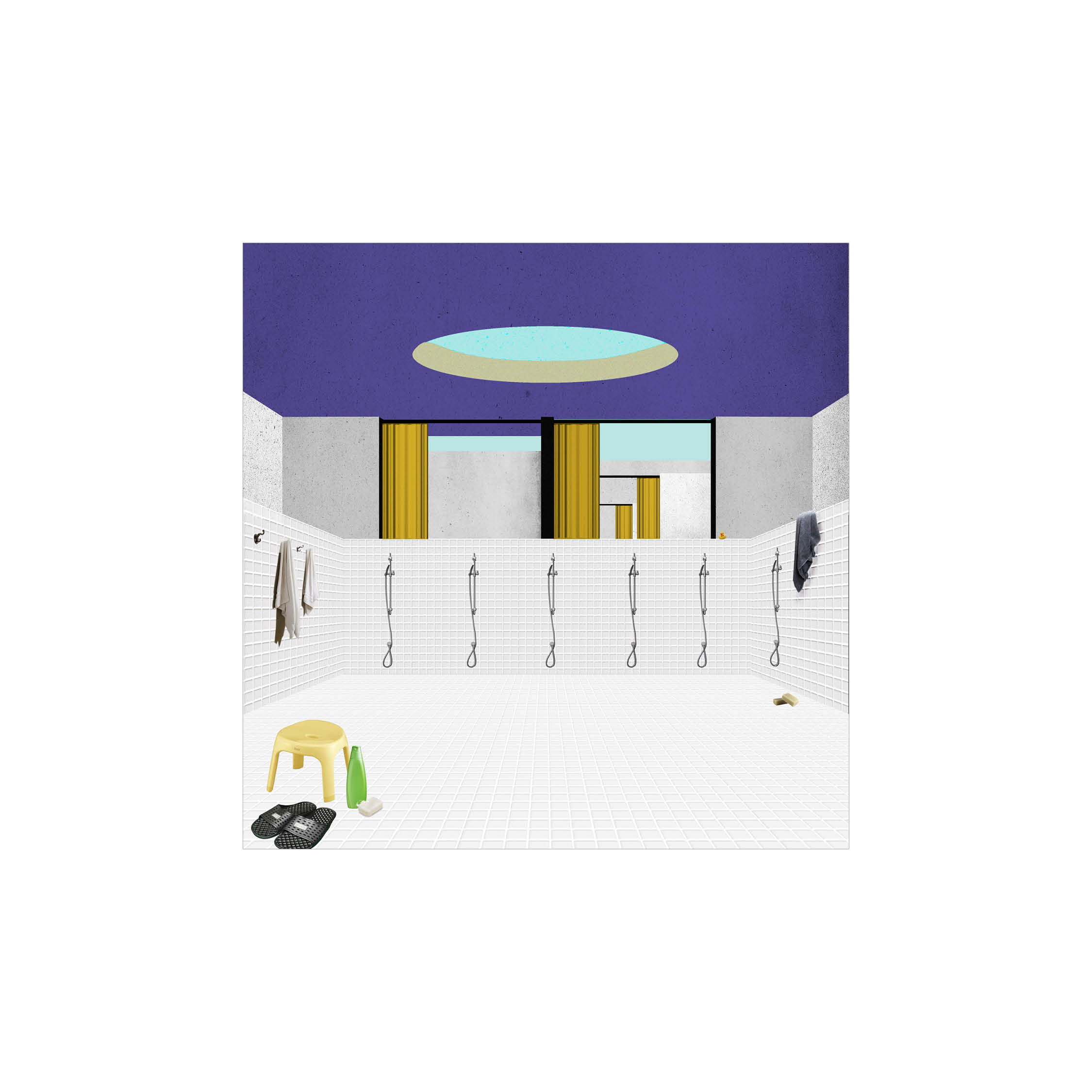

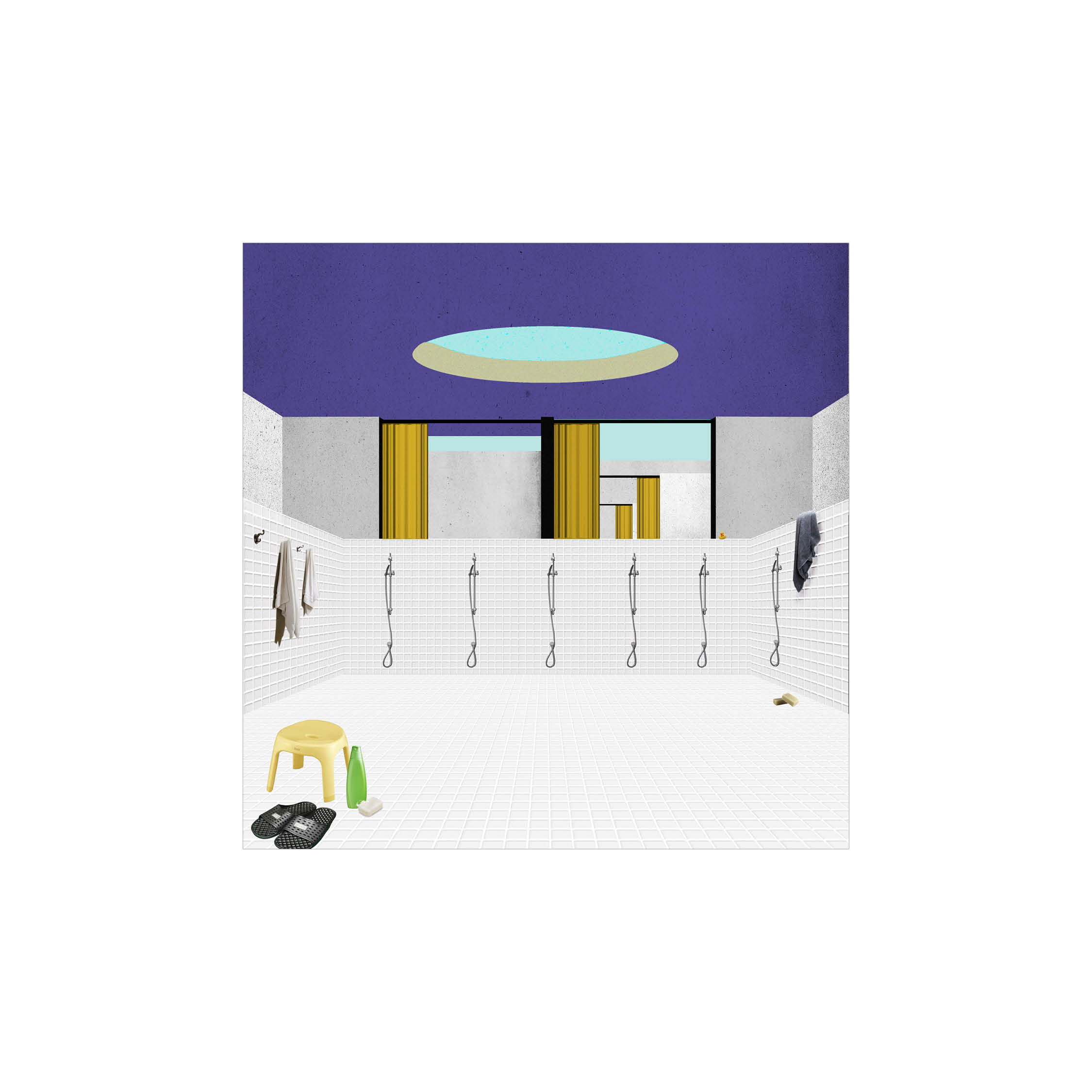

unit︎ communal kitchen ︎ jimjibang ︎ communal outdoor space

The project for the district of South of

Market (SOMA) in San Francisco caters to the workaholic culture that exists in

the tech industry by offering work and live spaces that prioritize shared

living spaces. An informal setup of lounge spaces provides the inhabitant with

generous opportunity for repose. Composed of a ground level of loose work space

and communal housing units above, the project challenges traditional notions of

domestic space.

Man’s relation to contemporary notions of domestic space is highly rooted in segregation. The formation and organization of politics within societal groupings, including that of the family, have been established for the intention of efficiency and economy. Boundaries that have been formed as a result, such as that of the atomized nuclear family, have in turn firmly structured specific modes of domestic space. The domestic realm has been reduced to a controlled place of comfort, where static conventions are not contested. The individuation of people as such has followed by housing typology that addresses the need for boundary – in the case of the nuclear family, the single family house.

The potential to destabilize traditionally constructed ideas of domestic space, and the suggestion of the possibility of new modes of lifestyle require an understanding, revisiting, and rethinking of existing socio-political as well as architectural boundaries. Can loose architectural boundaries allow for the dissolution of socially constructed relations? The wall, a basic architectural element, is the physical manifestation that assumes responsibility for privacy. Walls create enclosure – rooms, which are then given functions, and used accordingly. Today, the bedroom is used for sleeping, relaxation, and sexual intercourse—a private space, and a defining component of the domestic realm. In housing economics, the bed is used as metric to quantify inhabitants within a dwelling. Thus, a house without a bed-room, or a house with a room comprised of bed challenges fundamental ideas of domesticity. Who will use this space? And what is the renewed function of such a space? Does architecture have the capacity to intervene and undermine such principles, and provide a space for an unscripted politics, or perhaps a non-political space?

SOMA is highly saturated with start-up companies and incubators, which aim to connect people and offer shared experiences and amenities both in virtual and physical platforms. The culture of such companies, as was seen during a visit to the Facebook headquarters, is of extreme hyper-sharing of space. The worker shares this space, and subsequently confines himself to a solitary capsule as dwelling. Within this ethos is a blurring of boundaries between work and live space. A paradoxical phenomenon has risen out of this model – sharing of space occurs online and in the work environment, and atomization elsewhere.

Though active in the virtual realm, SOMA’s urban fabric is in fact empty. Between the bounds of the city center, waterfront, and freeway networks lie an array of dilapidated and underutilized low-rise, non-residential warehouses and commercial buildings.

A space such as this is simultaneously low-key and high-paced. The visiting inhabitant of the area is a passerby that will not be a permanent dweller. This dweller requires a negotiable space – one that can accommodate and alter per changing needs. Coupled with the incoherent parcelization of small and large lots, SOMA requires a strategy based on the pixel, an aggregate.

The existing ethos of fast-growing tech industry is retained by giving back to the ground floor a commercial-work space. Building on this is then a housing which conforms to the size of the given lot.

The unit is formed around a T-shaped wet wall. The surrounding space can be used per the inhabitant’s preference. Columns around the space allow potential for enclosure – light panels, glazing, or curtains provide various levels of privacy. A bathing area is provided for each unit. Cooking happens communally, within the in-between space that forms at the aggregate of four joint units. Tatami-like mats cover floors, welcoming informal repose. The ambiguity of this space destabilizes conventional norms and proposes a bed-room-less domestic space. A shared domesticity provides a generous communal space and shared activity, mainly in the form of cooking and bathing. With the growth of the aggregate, the system provides larger communal spaces, such as pools, libraries, basketball courts, gardens, etc. These spaces welcome a culture of sharing, something intrinsic in human sociology but unfortunately diminishing in contemporary lifestyles.

Already existing within semi-covert or experimental models, there exists in San Francisco a culture of communal living. There is a large community of people who are actively questioning their own domestic habits, and considering the possibility, meaning and potential of living together. This prototype aims to answer the desire for such a lifestyle and provides an articulated platform for shared domestic space. As a place transient dwelling, it allows people to experience living in a place with no traditional boundaries.

Here is an invitation for an architecturally-motivated phenomenological experience of un-scripted politics. In terms of construction, manufacture, and affordability, the stability and maintenance of such a system lies in a repeating rigid structure of prefabricated parts. By providing such a framework, and undermining typical notions of function-based rooms, the domestic plan is allowed to open. Further, providing the choice to organize his own space, the inhabitant is encouraged to consider preconceived notions of domestic reproduction and existing conditions of familial atomization. The typical idea of family (at least within American culture) is limited and limiting. With a rethinking of domestic ideologies, there is not only a disruption of function-based rooms but also a dissolution of gender-specific domestic roles, as well as preconceived and constructed social relations and hierarchies.

Man’s relation to contemporary notions of domestic space is highly rooted in segregation. The formation and organization of politics within societal groupings, including that of the family, have been established for the intention of efficiency and economy. Boundaries that have been formed as a result, such as that of the atomized nuclear family, have in turn firmly structured specific modes of domestic space. The domestic realm has been reduced to a controlled place of comfort, where static conventions are not contested. The individuation of people as such has followed by housing typology that addresses the need for boundary – in the case of the nuclear family, the single family house.

The potential to destabilize traditionally constructed ideas of domestic space, and the suggestion of the possibility of new modes of lifestyle require an understanding, revisiting, and rethinking of existing socio-political as well as architectural boundaries. Can loose architectural boundaries allow for the dissolution of socially constructed relations? The wall, a basic architectural element, is the physical manifestation that assumes responsibility for privacy. Walls create enclosure – rooms, which are then given functions, and used accordingly. Today, the bedroom is used for sleeping, relaxation, and sexual intercourse—a private space, and a defining component of the domestic realm. In housing economics, the bed is used as metric to quantify inhabitants within a dwelling. Thus, a house without a bed-room, or a house with a room comprised of bed challenges fundamental ideas of domesticity. Who will use this space? And what is the renewed function of such a space? Does architecture have the capacity to intervene and undermine such principles, and provide a space for an unscripted politics, or perhaps a non-political space?

SOMA is highly saturated with start-up companies and incubators, which aim to connect people and offer shared experiences and amenities both in virtual and physical platforms. The culture of such companies, as was seen during a visit to the Facebook headquarters, is of extreme hyper-sharing of space. The worker shares this space, and subsequently confines himself to a solitary capsule as dwelling. Within this ethos is a blurring of boundaries between work and live space. A paradoxical phenomenon has risen out of this model – sharing of space occurs online and in the work environment, and atomization elsewhere.

Though active in the virtual realm, SOMA’s urban fabric is in fact empty. Between the bounds of the city center, waterfront, and freeway networks lie an array of dilapidated and underutilized low-rise, non-residential warehouses and commercial buildings.

A space such as this is simultaneously low-key and high-paced. The visiting inhabitant of the area is a passerby that will not be a permanent dweller. This dweller requires a negotiable space – one that can accommodate and alter per changing needs. Coupled with the incoherent parcelization of small and large lots, SOMA requires a strategy based on the pixel, an aggregate.

The existing ethos of fast-growing tech industry is retained by giving back to the ground floor a commercial-work space. Building on this is then a housing which conforms to the size of the given lot.

The unit is formed around a T-shaped wet wall. The surrounding space can be used per the inhabitant’s preference. Columns around the space allow potential for enclosure – light panels, glazing, or curtains provide various levels of privacy. A bathing area is provided for each unit. Cooking happens communally, within the in-between space that forms at the aggregate of four joint units. Tatami-like mats cover floors, welcoming informal repose. The ambiguity of this space destabilizes conventional norms and proposes a bed-room-less domestic space. A shared domesticity provides a generous communal space and shared activity, mainly in the form of cooking and bathing. With the growth of the aggregate, the system provides larger communal spaces, such as pools, libraries, basketball courts, gardens, etc. These spaces welcome a culture of sharing, something intrinsic in human sociology but unfortunately diminishing in contemporary lifestyles.

Already existing within semi-covert or experimental models, there exists in San Francisco a culture of communal living. There is a large community of people who are actively questioning their own domestic habits, and considering the possibility, meaning and potential of living together. This prototype aims to answer the desire for such a lifestyle and provides an articulated platform for shared domestic space. As a place transient dwelling, it allows people to experience living in a place with no traditional boundaries.

Here is an invitation for an architecturally-motivated phenomenological experience of un-scripted politics. In terms of construction, manufacture, and affordability, the stability and maintenance of such a system lies in a repeating rigid structure of prefabricated parts. By providing such a framework, and undermining typical notions of function-based rooms, the domestic plan is allowed to open. Further, providing the choice to organize his own space, the inhabitant is encouraged to consider preconceived notions of domestic reproduction and existing conditions of familial atomization. The typical idea of family (at least within American culture) is limited and limiting. With a rethinking of domestic ideologies, there is not only a disruption of function-based rooms but also a dissolution of gender-specific domestic roles, as well as preconceived and constructed social relations and hierarchies.